I was at an event recently when I began talking with another Minnesotan about a school district near his home. The gist of his words ran something like this:

“’We need a bigger school to help the kids learn,’ the district says! Then they say, ‘Now we need an acre of land for every child so their academic performance improves!’”

I chuckled at this last statement, assuming he was using hyperbole, but then I stopped and thought about it. “Who knows?” I said. “That might actually help if each acre was used to get students out to work the land!”

My statement was in earnest. After all, forest schools—learning environments where children spend most of their time outside—are increasing in popularity and have shown themselves to be effective in boosting children’s immunities and enhancing cognitive skills, and may even diminish behavior problems.

Such improvements are merely common sense. After all, who doesn’t feel better than when they get outside, clear their minds, and tire their bodies with productive, physical labor rather than simply sitting in a chair in front of an electronic device all day?

This idea was one I accidentally tested myself a few days ago. I woke up in a foul mood and, needing a change of pace, unleashed myself on the weeds in my cucumber bed for an hour before heading back to my laptop. That time outside not only lightened my mood, but also cleared my thinking, allowing ideas and analogies to begin popping off in my head, which I was then able to reinvest back into my work.

The usefulness of the land and the physical labor it takes to tend it is one that author Wendell Berry wrote about extensively.

“One of the most important resources that a garden makes available for use is the gardener’s own body,” he wrote in The Gift of Good Land. “At a time when the national economy is largely based on buying and selling substitutes for common bodily energies and functions, a garden restores the body to its usefulness—a victory for our species.” He concludes: “A garden gives the body the dignity of working in its own support. It is a way of rejoining the human race.”

Now, Berry was likely writing those words for an adult audience … but don’t they apply to children just as well?

These days, it’s not uncommon for children to sit in a classroom for eight to nine months every year, surrounded by their peers, connected to electronic devices, and told to sit relatively still for hours each day. Add to the fact that many of these same children go home and spend the rest of the day scrolling through their devices, is it any wonder that our schools are filled with behavioral problems and a lack of focus galore?

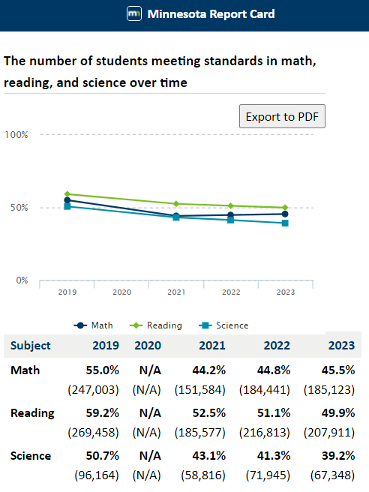

Consider the chart below, which shows statewide proficiency rates in reading, math, and science for the last five years in Minnesota. Each subject area dropped by about 10 percentage points in the last five years—and given past history, the next five years are likely to see those proficiency rates drop another 10 percentage points.

What would it do for our students—and their behavior, interactions with others, and grades or learning in general—if we got more of them out into nature, away from the bells and whistles of institutional schooling and the blue screens of tech, to work in the earth and breathe free?

Given what my own brief experiment in the garden taught me, I’d wager that it would do them worlds of good. They would feel productive and valuable, their angst would be driven away, and their brains would get the airing they need in order to do their schoolwork in fast order.

Now, granted, we can’t change the whole system on a dime and turn every mammoth district school into a farm school or give each child an acre of land on which to work. But we can give students and parents Education Savings Accounts (ESAs).

What in the world do ESAs have to do with giving children the opportunity to get out and work outdoors? Simple. They provide $7,000 for each student to use toward the educational option of his or her choice.

Assigning funds to students rather than schools allows parents to vote with their feet. If they want their children to be more than classroom automatons for the rest of their childhood, they can spend their $7,000 on innovative schools—such as micro-schools—that utilize a smaller, more flexible environment (which can easily include the outdoors and physical activity) in their school day.

And the more parents put their children in these innovative schools, the more likely we will see behavioral problems diminish and reading and math proficiency levels rise as children get a new lease on life while living and working in a natural environment.

—

Image Credit: Pxhere

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)