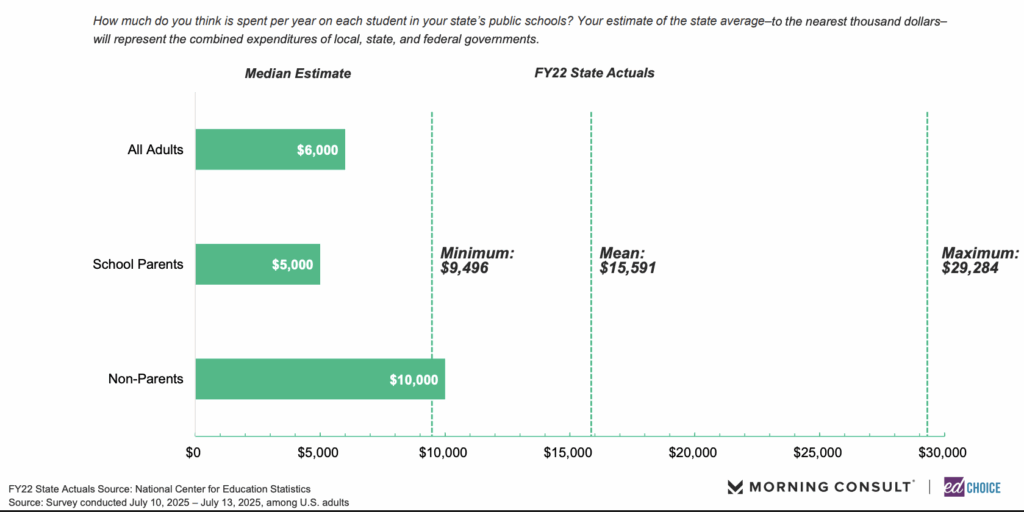

When asked to estimate how much their state spends per public school student, parents and other adults guessed $5,000 and $6,000, respectively, both significantly under the average across all states ($15,591 using FY 2022 data) and even well below the lowest spending state, Utah, at $9,496 per student.

A national July survey by Morning Consult on behalf of EdChoice polled 2,250 adults and 1,300 school parents on a variety of education-related questions, including public school funding. Non-parent respondents estimated public school spending was around $10,000 per student, a guess that landed within actual spending ranges.

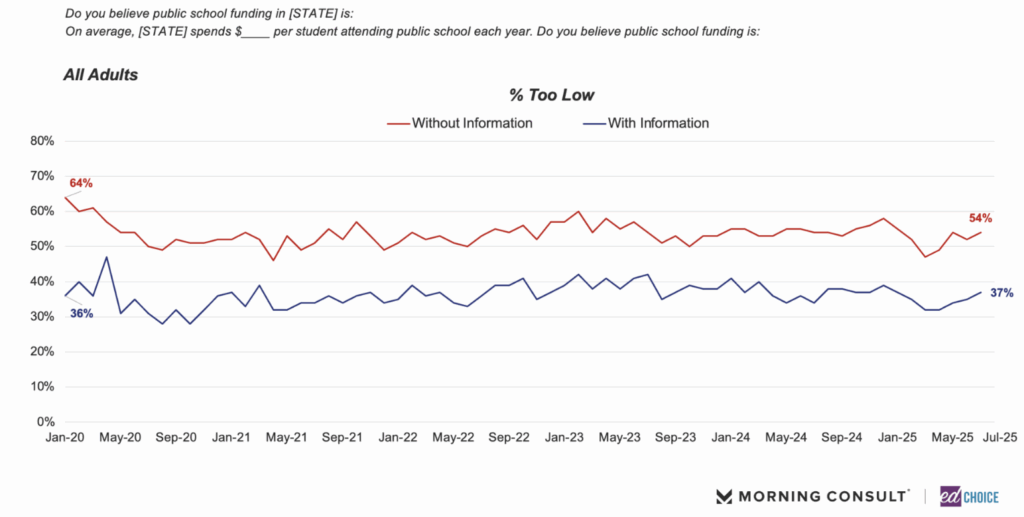

Respondents were also asked whether they thought public school funding in their state was too low, too high, or about right. Without any information on how much their state spent per public school student each year, 54 percent of the general public said funding was “too low.” With information on how much their state spent, the percent of Americans saying funding was “too low” dropped to 37 percent — a decrease of 17 percentage points — and the percent to say funding was “too high” increased 10 percentage points.

According to the Minnesota Department of Education’s latest numbers, Minnesota’s spending per student as measured by average daily membership (ADM) was $16,650 for FY 2024. (This varies by district.) Beginning with FY 2026, the basic formula allowance, which is the basic general education revenue component for school districts, will increase automatically each year at the rate of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) within a band not less than a two percent increase over the previous year or greater than a three percent increase over the previous year.

Over the last 20 years, FY 2004 to FY 2024, combined revenue per ADM has increased 106 percent, exceeding inflation by 2 percent per year over that time period. Meanwhile, average daily membership decreased by 3.2 percent over the 20-year period.

It is a long-standing debate in education how much money matters. Education Minnesota, the teachers’ union, would have you believe that education has been grossly underfunded for years and not kept pace with inflation. (Watch for my soon-to-be-released policy brief that digs into this misleading narrative.) But even if the education fund was to hit the “magic number,” should that specific price tag ever be provided, what would that mean for Minnesota?

It depends.

More money doesn’t guarantee better achievement results because how money is spent matters far greater than how much is spent. Prominent education economist Eric Hanushek has long argued this as well.

We can observe this at a high level by comparing reading performance and per pupil spending between Minnesota and other states. Its achievement results lag a number of lower-spending states that serve similar student demographics. There are also examples of states that spend far more than Minnesota and have higher achievement results, and there are states that spend less than Minnesota and perform worse.

Making the case for increasing education funding is certainly someone’s prerogative, but it should be done in a transparent and accountable way. The state’s track record of return on investment for increased spending isn’t stellar. How will the dollars be used? Will they actually get to the students they are intended to help? How will this go-around of increased funding be different from last time? Or, perhaps, as other states have done, it’s time to focus less on inputs and more on policy decisions that produce meaningful outcomes.

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)