While compiling a list of individual, public-school districts in Minnesota the other day, I noticed something curious. My list consisted of around 330 districts … but the district numbers weren’t all consecutive.

The list started with Aitkin (District Number 1*), proceeded to Hill City (District Number 2), jumped to McGregor (District Number 4), and then to Anoka-Hennepin (District Number 11). The numbers continued jumping, eventually reaching Ada-Borup-West (District Number 2910).

“There must have been around 3,000 districts in Minnesota at one time,” I concluded, thinking that going from 3,000 to just over 300 was quite the reduction!

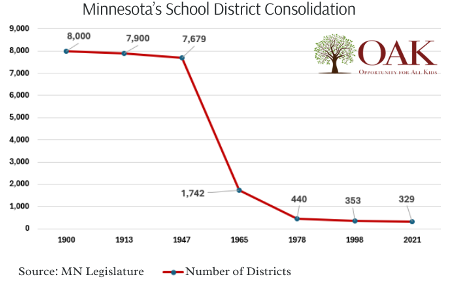

Turns out, I was wrong. There weren’t just 3,000 districts in Minnesota once upon a time. There were 8,000!

And the number of districts remained close to 8,000 until after World War II. After the war, the number of school districts in the state dropped by almost 6,000 over a period of roughly 20 years, according to the Minnesota Department of Education.

Why was the state so anxious to consolidate districts? The official reason given around the turn of the 20th century was that the small staff in the state education offices couldn’t maintain the right amount of contact with the many local districts. In other words, there were too many districts to control.

On a national level, officials encouraged district consolidation based on the idea that it was more economical or efficient. Larger districts wouldn’t have to reduplicate as many administrative or educational roles, so education costs would shrink while students would have access to more opportunities.

While this seems logical in theory, things didn’t play out that way in real life. Despite this consolidation, spending continued to rise, and researchers “began investigating whether larger districts really did spend less per pupil,” a report from the Mackinac Institute explains. And as districts grew larger, education moved further and further away from local communities.

Today, we’re seeing the effects of an ever-greater centralized education system, particularly in Minnesota as state legislators enforce more education mandates from the top down. In essence, state lawmakers are almost turning the whole state into one big district, and teachers and superintendents are not happy with these developments.

We live in a time when education options and innovations are proliferating. Given that, perhaps it’s time we consider reversing course on district consolidation and allow education to become ever more local.

What would be some benefits of doing so?

As mentioned previously, less district consolidation would likely mean more local control. And local control brings benefits to teachers, parents, and students.

For teachers, smaller school districts offer more freedom from top-down mandates. Consolidated districts often mean bigger schools, which in turn make teachers simply a cog in the broader education system, where their voices are lost, their hands tied, and their innovative ideas squelched. If we reversed district consolidation, we may also begin to see teacher autonomy expand.

Less district consolidation returns education to local communities, giving parents a greater say in their children’s education. When a district is smaller and local, parents are much more incentivized to get involved, ensuring that their ideas and needs are heard, and their presence and support is felt by those teaching in the trenches. In so doing, parents also take back control from unions.

For students, smaller schools and smaller districts mean that they become known entities, rather than just bodies that warm seats. Less anonymity can result in fewer behavior problems, as students realize that their teachers care about them—and that word of misbehavior can also make its way back to their parents much more quickly.

Of course, such massive decline in districts over the years would be hard to reverse. But that’s why it’s interesting that the push toward smaller, more local, more individualized education may already be happening on its own, leaving the state and its behemoth districts behind. This is seen in the surge toward education alternatives like micro-schools, private schools, homeschool co-ops, and even smaller, community-oriented charter schools.

Why not expedite the return to smaller, more localized forms of education even more by offering Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) that allow dollars to follow students to the school of their choice?

—

Image Credit: Nick Number, CC By 4.0

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)