We’ve reached the home stretch of the school year, and by now, most parents, teachers, and even students understand the lay of the land in their schools. It’s pretty apparent whether classrooms are under control, whether students are learning, and whether teachers are getting burnt out by top-down mandates and demands.

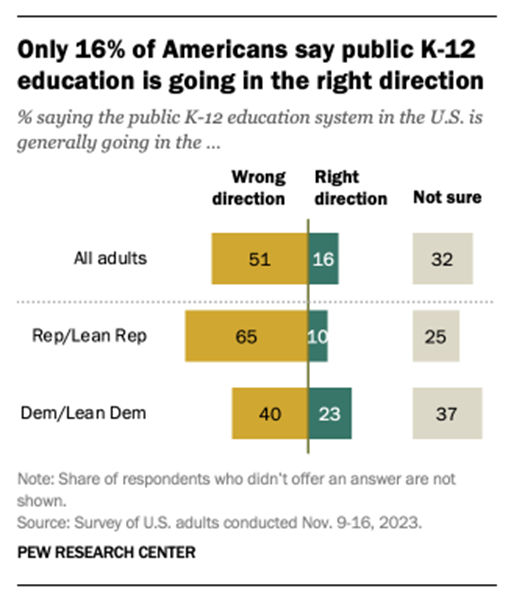

Unfortunately, it seems the individuals smart enough to decipher these signs aren’t liking what they’re seeing, for according to a new poll from Pew Research, only 16% of Americans believe the public education system is going in the right direction.

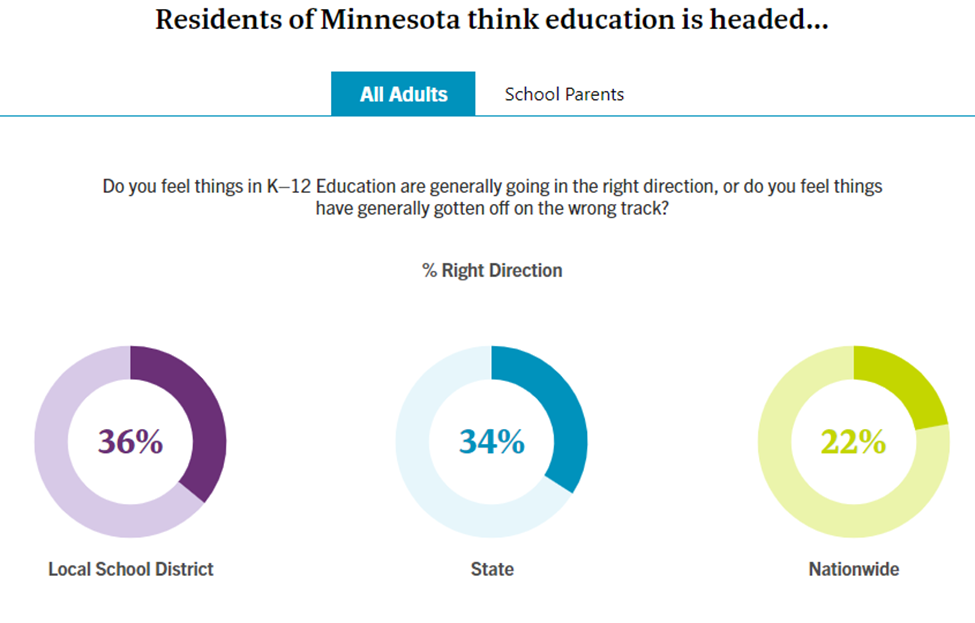

That dissatisfaction isn’t only at the national level, however. Recent polling from EdChoice finds that roughly 65% of Minnesota adults think the state’s K-12 education is also heading in the wrong direction. That’s quite a switch, because for years Americans have frowned upon the direction public education was going nationally, while insisting that their own local district was just fine. Now it appears that displeasure about education on statewide and local levels is catching up to national sentiments.

Why is that?

Digging deeper into Pew’s polling offers a clue. One of the reasons given by both Democrats and Republicans for why public education is heading in the wrong direction is that “schools are not spending enough time on core academic subjects” such as reading, math, and science.

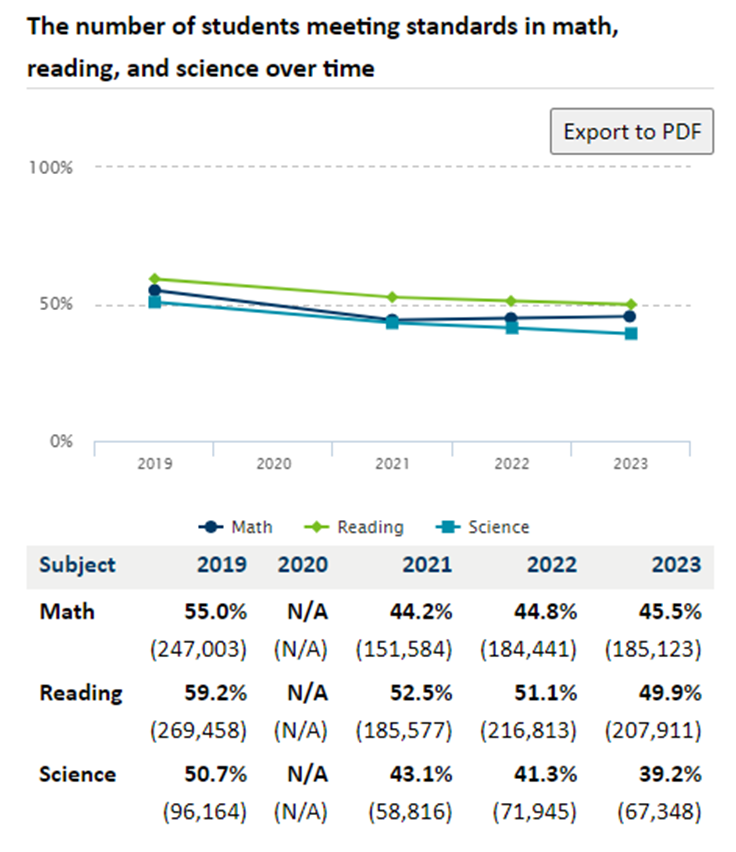

That seems to be consistent with education data in Minnesota. Statewide, only 50% of students are proficient in reading, only 46% are proficient in math, and only 39% are proficient in science.

What’s preventing this core instruction from happening? One possibility is that student misbehavior is escalating. The more time teachers must deal with an unruly class, the less time they have to focus on instruction.

Another possibility is the mandates coming down from bureaucrats in St. Paul. When those not in the classroom are calling the shots, they frustrate teachers, forcing them to spend precious instruction time jumping through unnecessary hoops.

A third possibility is that schools have shifted their mindset, believing that it’s more important for classroom instruction to focus on a student’s mental health than academic basics. This is partially seen through the concept of social-emotional learning, or SEL.

“SEL is the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions,” runs the definition from Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

On the surface, this sounds great. After all, who doesn’t want children to be socially and emotionally well-adjusted? Unfortunately, such an interpretation of this definition doesn’t appear to be the real goal of SEL learning.

“SEL advances educational equity and excellence through authentic school-family-community partnerships to establish learning environments and experiences that feature trusting and collaborative relationships, rigorous and meaningful curriculum and instruction, and ongoing evaluation,” the CASEL definition continues. “SEL can help address various forms of inequity and empower young people and adults to co-create thriving schools and contribute to safe, healthy, and just communities.”

Author Abigail Shrier gives us a glimpse of what this definition means practically in her new book, Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up. According to Shrier, schools have placed a decided emphasis on feelings in recent years, turning classroom time into a type of group therapy session where students are encouraged to share their problems from home and life with everyone else. Instead of helping kids get past their difficulties, Shrier explains, SEL seems to help them wallow in their problems, taking their focus off their schoolwork and putting it on their own personal issues.

But SEL can be even more harmful to children, for in creating those “trusting and collaborative relationships” amongst school peers and staff, the relationships between students and their parents are eroded. Shrier says that some SEL exercises even encourage a form of spying on parents and families, information which is then shared at school:

The casual denigration of parents to their children turns out to be a signal feature of social-emotional learning. Mom and Dad are only ‘caregivers,’ service providers, and incompetent ones at that, who might even be harmful to their kids’ mental health. They present the obstacles to children’s flourishing, like ‘parent negativity.’

This isn’t merely teachers’ lounge banter, public servants blowing off steam while abusing the communal microwave with a Tupperware of tuna casserole. It’s why they’re always sending out ‘tips’ to parents on how to talk to our kids about the news or even life events. It’s the reason they’ve created an entire social-emotional ‘at home’ lessons component—for parents to practice with kids. All predicated on the belief, to borrow the language of one lesson, that parents are often ‘roadblocks’ to kids’ flourishing.

Let’s face it. Parents want the best for their children. They want to send them to a good school—to experts who know their stuff and can pass along high-quality academic knowledge to their children, helping them succeed in becoming adults.

Yet when people see academic proficiency hovering around 50%—and even lower—in districts around the state, and then when they find out that classroom instruction is feelings-based and may even be pitting their children against them as parents, is it any wonder that Americans think public education is headed in the wrong direction?

Minnesota’s public education system clearly needs an overhaul. But while we’re waiting for that to happen, which could take a decade or more, shouldn’t we give current parents the opportunity to get their kids out of that crumbling system and into a classroom that will actually teach the academic basics?

The only way for that to happen is to establish Education Savings Accounts for students. In doing so, all parents have the opportunity to give their kids that chance — not just the affluent.

—

Image Credit: Flickr-woodleywonderworks, CC BY 2.0

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)