OAK and others have been alerting Minnesotans to the deeply troubling reality that the Minnesota Department of Education’s assessments are finding only 49.9% of all public school students and only 52% of public high school sophomores proficient in reading – for two years in a row.

Here is the chart taken directly from the Minnesota Department of Education’s (MDE) website for all public school students:

For Minnesotans who remember when our public education system was one of the best in the nation, these numbers seem unbelievable. How is it that Minnesota has gone from one of the best states to a 49.9% reading proficiency rate?

That question comes up a lot when sharing the numbers with parents and the public. So do these: Is it real? How do we know?

The results of a failing education system in Minnesota and across the country are bubbling to the surface with greater and greater frequency, making it difficult to ignore the changes people are seeing.

Locally, conversations with college professors, employers, and others reveal a distressing lack of preparedness for students graduating from high school and going to college, the military, a trade school, or the working world. They’re simply not ready.

This week, in an article titled, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” The Atlantic pulls back the curtain on the results of our failing education system at America’s highest educational levels. Here’s how it opens:

Nicholas Dames has taught Literature Humanities, Columbia University’s required great-books course, since 1998. He loves the job, but it has changed. Over the past decade, students have become overwhelmed by the reading. College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books.

…

… the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.

‘“’My jaw dropped,’ Dames told me. The anecdote helped explain the change he was seeing in his students: It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how. Middle and high schools have stopped asking them to.

The article reminds of me of the warning a Minnesota teacher wrote ten years ago.

Here is what Kim Dallas, at the time an English teacher at Rosemount High School in Rosemount, Minn., had to share with Star Tribune readers in 2014:

I teach high school English, and I am begging you to please read to your children. Read everything. Read baby books when they are babies. Read picture books when they are older. Ask your middle-schoolers to read street signs, billboards and marquees during every car ride. Ask your teenagers to read your water bills, junk mail, newspapers, magazines, recipes and catalog descriptions. Read everything like your life depends on it.

Why? Because your children can’t read.

We are in the midst of one of the greatest literacy crises ever encountered, and we are fighting an uphill battle. Every day I experience firsthand what it means to be illiterate in a high school classroom. At best it means sleeping away a unit; at worst it means depression or aggression. Average students with average abilities can fervently text away, but they cannot read.

Recently, I gave a unit test where students could use all their notes and their short story on the test (not my standard practice). The results: abysmal. I didn’t think the test was too difficult until I started doing some investigating and made a shocking discovery. They couldn’t even read the test. Don’t think it’s your child? Ask your high school teenager to define the following: superior, ridicule, flippant or mundane.

Now imagine your child taking the ACT or SAT. Now what?

I teach nearly 200 high school juniors each day. If we give them all the same book to read, they often do not read it. Ask them why, and they say: ‘It’s boring.’ Translation? ‘It’s too hard.’ They also may say they have no time. As educators, we can only do so much with the limited resources we have. I understand I have an obligation to teach in an exciting and rewarding way, but my tech-savvy students are beating me down, and I need your help.

What can you do? Model reading in the home. Visit the library. Go to the bookstore. Share your reading experiences with them. Encourage them to read their assigned work. Offer your help with comprehension. If you struggle with reading, please share how you face this difficult challenge with success. They need your help. I need your help. To succeed in school, students must read on their own. Our future depends on it.

At the time Kim Dallas wrote her warning, Apple Valley’s 10th-grade reading proficiency rate was 70%. Now it’s at 52% for the entire state.

How is this possible? Simply put, the education system has failed and it simply runs kids through to graduation, whether they’re ready or not. Despite the efforts of teachers like Kim Dallas, the system now exists for itself, not the students or the common good. It cannot adapt to the needs of the students.

In Minnesota, our high school graduation rate has been hovering around 83% for several years, yet the most recent 10th-grade reading proficiency assessments from MDE show only 52% of 10th-grade students are proficient in reading for two years in a row. Math proficiency in 11th grade is even worse. In 2023 it was 36% and then in 2024 dropped to 35%.

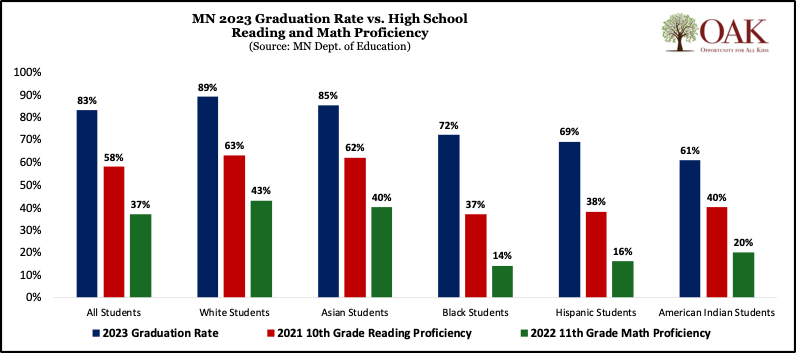

Here is an examination of the graduating class of 2023 (for all students and then broken out by race), which examines how each cohort performed on both their 10th-grade reading and 11th-grade math assessments.

As you can see, the overall graduation rate for the class of 2023 was 83%, but the reading proficiency of that class in their 10th-grade assessments (2021) was only 58%. And for the class of 2023’s math assessments (2022), only 37% were proficient as high school juniors.

The situation is even worse when we look at students of color. 72% of Black students graduated in 2023, but only 37% were proficient in reading and only 14% were proficient in math. Similarly, for Hispanic students in 2023, 69% graduated, but of that graduating class only 37% were proficient in reading and 16% proficient in math.

Stepping back, is that not one of the greatest injustices to commit against a student? The education system tells the kids they’re ready and gives them a diploma. The young adult goes out into the world only to discover that actually they are not ready.

I have heard from countless parents and grandparents – even legislators! – who had a child go through high school earning As and Bs, got accepted to college, and then washed out almost immediately because the student could not read or write at the necessary level. Those young adults are often forced to attend a community college for two years to receive the remedial education they should have received in high school.

And according to The Atlantic, that’s happening even in our elite colleges and universities.

The education system is simply not doing its job. When schools inflate grades and move kids along as if on a conveyor belt, parents are left in the dark about what their kids really need and by the time the problems are discovered, it is often too late.

The humiliation, the expenses, the missed opportunities, they are all unacceptable. These are the lives of young people to whom we entrusted the public education system to provide an education and help them be ready for the next stages of life. While some may rise above the challenge, many are going to be left permanently behind.

Furthermore, it doesn’t take much to realize the grave danger this situation poses to the health and welfare of our families, communities, state, and nation.

The decline in Minnesota’s public education system has been ongoing for a decade or more. What happens if we allow this crisis to continue for another decade? What do our families, communities, and state look like if half the adult population struggles to read and can barely do math?

Thinking through the broad ramifications is a bit like looking into the abyss.

On the positive side, we do not have to be locked into this particular education system or spend decades fighting with the teachers’ unions to fix it.

With school choice and Education Savings Accounts (ESAs), the state would still ensure the education of the public but change the funding model for it. Currently, the state allots a minimum of $7,000 per student. Those funds “follow” the student to a public or charter school.

With school choice, that $7,000 would be deposited in an Education Savings Account (ESA) managed by the state and the parents or guardians would be free to use those funds on any eligible school or educational setting of choice – not just the local public schools or a charter school.

In this way, the state continues to fund the education of the public while putting parents in the driver’s seat of where those funds are directed, giving all families the freedom and resources to find the best schools for their kids.

In doing so, many different educational approaches and curriculums can be offered to families. Not every kid is going to fit into the box that is the current, failing system.

There are roughly 870,000 public school students in Minnesota. If half of them are struggling to read, that’s 435,000 students who need a solution right now.

School choice and ESAs are the solution that can be immediately enacted in the next legislative session, giving hundreds of thousands of Minnesota students the lifeline they need to an education that will truly prepare them for life. Nearly 20 states have already made the jump, it’s time for Minnesota to join them.

If you’re a parent and want the freedom to find the best education for your child, it’s time to make your voice heard. Start talking about the opportunity with friends, family, and associates. And start talking to candidates and legislators about what can and should be the next evolution in public education.

—

Image Credit: PickPik

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)