The number of principals and assistant principals in Minnesota public schools is up again even though they served fewer students, according to state data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

The most recently available principal data shows that Minnesota public schools added over 100 assistant principals and principals from fall 2022 to fall 2023, increasing by 3.7 percent despite public school enrollment declining over that same time period.

From fall 2019 (pre-COVID) to fall 2023, principal and assistant principal growth was over 11 percent. Public school enrollment dropped just under three percent (2.6 percent) during that period.

Perhaps the infusion of federal COVID relief funds sent Minnesota’s public school system into a hiring spree over the last few years, as district administrative staff also grew during this time. But as I explain here, the staffing surge also existed pre-COVID.

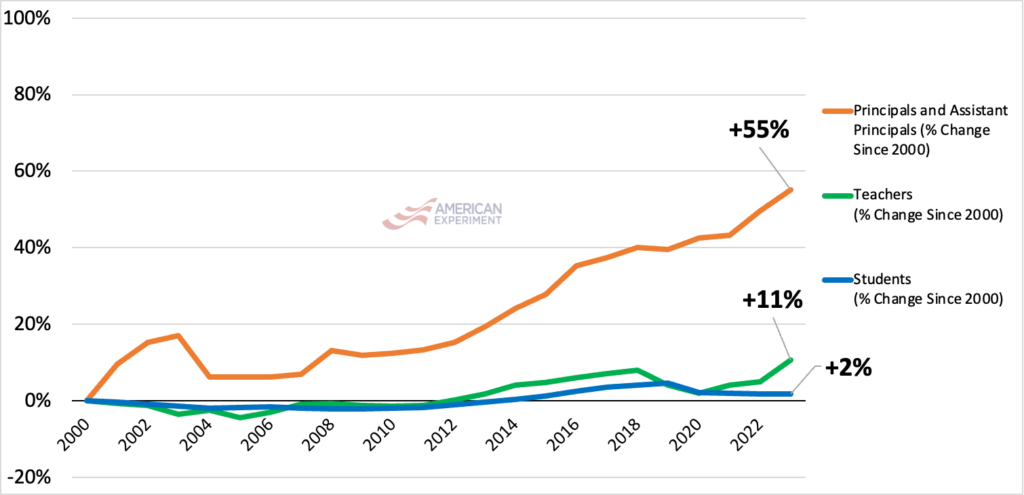

In fact, from 2000 to 2023, there has been a 55 percent increase in principals and assistant principals compared to a 2 percent increase in student growth and an 11 percent increase in teachers. We see similar trends nationwide — principal and assistant principal growth at 39 percent, student growth at 5 percent, and teacher growth at 9 percent.

Growth in Principals, Teachers, and Students in Minnesota Public Schools, 2000-2023

For schools that face the one-two punch of enrollment loss and the end of federal COVID aid, tough staffing decisions will have to be made if one-time funds were used for ongoing expenses. What positions get cut? Who gets to stay? Non-teaching staff aren’t cheap. According to the Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board (PELSB), the average middle school principal salary for the 2023-24 school year came in at $134,542.

Is there research that suggests added non-teaching staff yield some student improvements? Yes, but at what cost? And compared to what other options? Is adding non-teaching staff the best use of limited resources for students?

This school staff hiring spree is what research professor Marguerite Roza at Georgetown University refers to as the “big bet” that public education has been pursuing for 50 years — going all-in on increasing education staffing to improve schools. Besides being financially unsustainable, it has “crowded out other potential big-bet investments that might let us do more for students with the dollars at hand,” such as increasing learning time or raising teacher salaries, Roza explains.

Will the “big bet” on staffing continue? Or will the decades of time and opportunity cost involved finally be enough to break the cycle of bureaucracy influencing the non-teaching staffing decisions of too many public schools in America?

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)