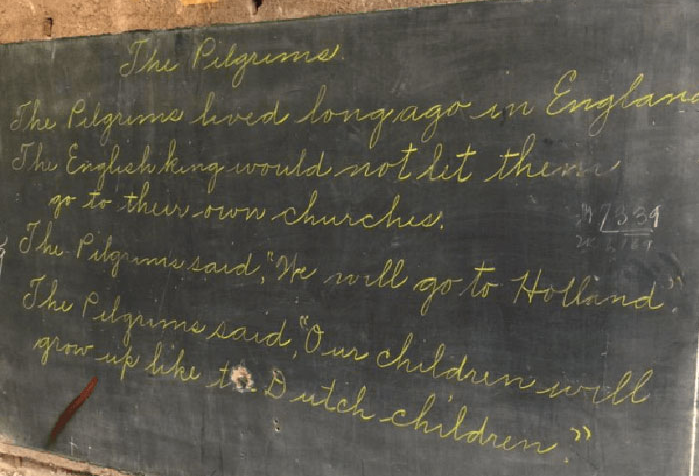

Once upon a time, celebrating Thanksgiving was a regular part of the public school calendar. Proof of this was found several years ago when a remodel of an Oklahoma City classroom uncovered chalkboards from 1917. These chalkboards were likely covered up around Thanksgiving time, for they contained images of Pilgrims and The Mayflower, along with narratives about why the Pilgrims fled England for the New World.

Today, however, the story of the Pilgrims seems largely absent from today’s classrooms. In fact, a 2019 article in Education Week even referred to the traditional Thanksgiving story as a “myth,” while a 2020 article from Today used the terms “historical fallacy,” “white supremacy,” and “colonization” in connection with the first Thanksgiving. For those who value such terms as multiculturalism and diversity, it seems the narrative of the first Pilgrim settlers and the native peoples who helped them can’t be buried fast enough.

But what does this new narrative—i.e. Pilgrims as white supremacists and the story of the first Thanksgiving as an historical fallacy—do to our country, and in particular, our public schools?

The late author Neil Postman sheds some light on that topic in his book The End of Education.

“The idea of public education,” Postman wrote, “depends absolutely on the existence of shared narratives and the exclusion of narratives that lead to alienation and divisiveness. What makes public schools public is not so much that the schools have common goals but that the students have common gods.”

Postman defines the word “god” in this sense as a “great narrative, one that has sufficient credibility, complexity, and symbolic power to enable one to organize one’s life around it.” By this definition, the story of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving definitely fits; indeed, it is a narrative whose symbolism was held up for hundreds of years as one to respect and appreciate for all who called America home.

Why are these common, positive narratives needed in our public schools? According to Postman, the reason is because public education creates a public rather than serving a public. “And in creating the right kind of public, the schools contribute toward strengthening the spiritual basis of the American Creed.” Such a mission is one endorsed and understood by everyone from Thomas Jefferson to John Dewey, Postman explains.

Wrapping up his argument, Postman states the following:

The question is not, Does or doesn’t public schooling create a public? The question is, What kind of public does it create? A conglomerate of self-indulgent consumers? Angry, soulless, directionless masses? Indifferent, confused citizens? Or a public imbued with confidence, a sense of purpose, a respect for learning, and tolerance? The answer to this question has nothing whatever to do with computers, with testing, with teacher accountability, with class size, and with the other details of managing schools. The right answer depends on two things, and two things alone: the existence of shared narratives and the capacity of such narratives to provide an inspired reason for schooling.

Step back and ask yourself those same questions. Our public schools seem to be doing their best to scrub traditional narratives from the classroom, replacing them with a multicultural one which crucifies our Founding Fathers and their Pilgrim predecessors as white supremacists and brutal colonizers.

But what kind of citizens is this new narrative producing? A look around at society seems to indicate that it is exactly the type of citizens Postman predicted it would produce: self-indulgent, angry, indifferent, and confused.

Such a realization should lead us to yet another one, namely, something is terribly wrong with public education today. We have public education, but it’s not education for the public, to paraphrase OAK’s Executive Director Devin Foley.

And if public education is not truly educating the public, then why do we continue to fund it with public dollars? Would it not be better to let those dollars follow each student, allowing parents to choose whether they want their children to go to schools with the more traditional narratives—the ones that bring Americans together, enabling them to rejoice in the heritage of their country—or the newer, multicultural narratives, which seem to only lead toward “alienation and divisiveness”?

Which of these narratives is your school promoting? It’s a wise and worthy question to ask this Thanksgiving.

—

Image Credit: Flickr-fivehanks, CC BY 2.0

![[downloaded during free trial]](https://oakmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/iStock-1430368205-120x86.jpg)